Cholera (Холера, Vibrio cholerae, الكوليرا)

What is the definition of cholera?

Cholera (Холера, Vibrio cholerae, الكوليرا) is an acute intestinal infection caused by Vibrio cholerae and characterized by severe diarrhea, dehydration and weight loss with the depletion of body liquids. Vibrio cholerae is a Gram-negative bacterium having the shape of a slightly curved rod.

Cholera is rare in the USA and other western industrialized countries. However, globally, cholera outbreaks in Asia have increased dramatically. In April 2017, an outbreak of cholera began in Yemen and remains ongoing as of July 2017.

The World Health Organization (WHO) considers the outbreak to be a real pandemic threat with its wide geographical distribution and rapid spread.[1]

The number of cholera cases in Yemen have increased after 27 April 2017. During May, 74k suspected cases were reported, including 605 deaths. By 24 June 2017, UNICEF and WHO estimated that the total number of cholera cases in Yemen since the outbreak of cholera in Yemen in October 2016 had exceeded 200k with 1,300 deaths, and that 5k new cases are reported daily.

What are the causes of cholera?

Cholera is caused by consuming food or drinking water contaminated with the bacterium Vibrio cholerae.

Pathogen

Vibrio cholerae biovar cholerae (Genome Passport: Vibrio cholerae 01, biovar cholerae), Vibrio cholerae O1 biovar eltor str. N16961 (Vibrio cholerae serotype O1 biotype El Tor strain N16961), Vibrio cholerae CIRS101, Vibrio cholerae O1 biovar El Tor str. Inaba RND18826, Vibrio cholerae O1 biovar El Tor str. Inaba RND18899, Vibrio cholerae O1 biovar El Tor str. L-3226, Vibrio cholerae B33, Vibrio cholerae O1 biovar El Tor str. Ogawa RND19187, Vibrio cholerae O1 biovar El Tor str. Ogawa RND6878

Epidemiology

How do you get cholera?

The source of infection:

In most cases, cholera is caught from the reservoir of infection to a susceptible host. A vehicle may passively carry the pathogenic environmental strains of vibrio cholerae from a natural environmental reservoir to another location. Moreover, contaminated food and water often pose a risk for travelers.

Vibrio cholerae is a member of the Vibrionaceae (a Proteobacterial family), which is commonly found in brackish or saltwater.

How is cholera spread?

Mechanism of transmission:

Cholera can be transmitted by Fecal oral route, most commonly by ingesting contaminated water (liquids), less commonly, it can spread through contaminated food, or by means of contact.

Cholera spreads from person to person by ingesting food sources that have been contaminated by poop (feces) from a person infected with cholera. Cholera can also spread through direct contact with an infected person (a sick person), or a carrier of vibrio cholerae bacterium. This occurs when an infected person touches or exchanges body fluids with someone else.

Clinical picture

Incubation period ranges from one to 6 days.

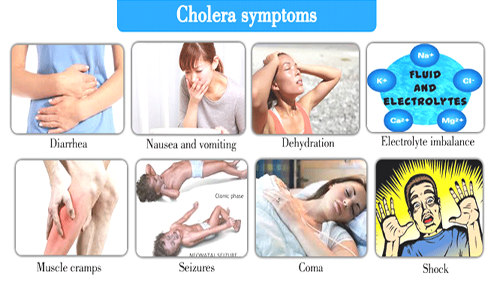

What are the symptoms of cholera?

Gastrointestinal syndrome

Frequent bowel movements (loose stools occurring from 5 to 50 times a day), abundant, sometimes appearing in the form of “rice water”, watery diarrhea with no pathological impurities, and without fecal odor and color. Abdominal pain is absent.

A compelling urge to vomit is characteristic, especially after the common early signs and symptoms of cholera (diarrhea).

Dehydration syndrome,

Severe dehydration results from the abundant loss of fluids in stool and vomiting. Common symptoms of severe dehydration include:

- Excruciating thirst

- Hoarse voice, possible aphonia

- Cyanosis and decreased skin turgor

- Retraction of the eyeballs

- Convulsions

- Decreased blood pressure (hypotension)

- Increased heart rate (palpitations)

- Shortness of breath (odushia)

- Oliguria

- Anuria

Intoxication syndrome is not characteristic (not expressed). Hyperthermia is absent. However, hypothermia may develop in severe conditions.

Although Dehydration and hypovolemic shock are the most severe complications of cholera, other life threatening problems can occur, such as:

- Severe hypoglycemia (low blood sugar).

- Severe hypokalemia (low potassium levels).

- Kidney failure or renal insufficiency.

Diagnosis

How to diagnose cholera?

1- Enrichment in 1% alkaline peptone water

Alkaline peptone water (APW) is an enrichment broth for isolating Vibrio cholerae from clinical samples and from suspected food and water samples. Culture of vomit, suspected food and stool material (feces) on selective bacteria.

Inoculate the APW bottle with stool specimen (liquid stool, fecal suspension, or a rectal swab) and incubate with the cap loosened at 37°C for 6 to 8 hours.

Inoculate 1 g (1 ml) of stool or rectal swab into 10 ml of sterile alkaline peptone water (APW) and incubate at 37°C for 6 to 8 hours

After incubation, subcultures to TCBS (thiosulfate citrate bile salts sucrose agar) should be made using one large loopful from the topmost surface of the broth.

It may not be necessary to enrich stool specimens, if the patient is passing liquid stool in very early stages of cholera

Thiosulfate citrate bile salts sucrose (TCBS) agar has an alkaline pH of 8.5 which suppresses growth of intestinal flora other than vibrio species. Vibrio species produce either yellow or green colonies on TCBS.

2- Serological methods.

Differential diagnosis

Differential diagnosis of cholera is carried with salmonellosis, dysentery, and food poisoning.

Treatment

How to treat cholera?

Pathogenetic therapy of intoxication caused by the endotoxin of Vibrio cholerae (The lipopolysaccharide, LPS).

Give antibiotics only to patients with severe dehydration.[4]

Use of antibiotics for the treatment of cholera

Begin antibiotic therapy after the patient has been rehydrated (usually in 4 to 6 hrs). Antimicrobial agents are typically administered for a period of 3-5 days.

Children under 5 years of age should also be given zinc for 10 days (10 mg/day for children under six months of age, and 20 mg/day for children 6 months and older).

Single dose antimicrobial therapy for cholera. A single dose of tetracycline (25 mg/kg; not to exceed 1 g/dose), doxycycline (7 mg/kg; not to exceed 300 mg/dose), furazolidone (7 mg/kg; not to exceed 300 mg/dose), or ciprofloxacin (30 mg/kg; not to exceed 1 g/dose) has been shown to be effective in reducing the duration and severity of diarrhea.[3]

Multiple dose antimicrobial therapy for cholera. A 3 – day course of ampicillin (50 mg/kg/d divided qid for 3 d; not to exceed 2 g/d), erythromycin (12.5 mg/kg 4 times a day, for 3 d; not to exceed 1 g/d), tetracycline (12.5 mg/kg 4 times a day, for 3 d; not to exceed 2 g/d), or doxycycline (2 mg/kg bid on day 1; then 2 mg/kg qd on days 2 and 3; not to exceed 100 mg/dose) has been shown to be effective treatment for cholera.[2][3][4]

Rehydration therapy: Trisol, Acesol, Chlosol.

In case of hyperkalemia (on the background of using large volumes Trisol) – switch to Disol.[2]

The volume of saline solution injected depends on the degree of dehydration. Set the rate of intravenous infusion in severely dehydrated patients at 50 mL/kg per hour within 4 hr (mild dehydration) or at 100 mL/kg per hour over 4 hr (moderate dehydration).[2][3]

In case of third or 4th degree dehydration, rehydration is carried out in two phases:

Phase 1 – Restore the lost amounts of fluids and electrolytes to their level before hospitalization.

Phase 2 – Restore the level of liquids and electrolytes to norm. Restoring normal hydration status should take no more than 4 hours.[2][3]

References

Verified by: Dr.Diab (July 1, 2018)

Citation: Dr.Diab. (July 1, 2018). Cholera Epidemiology Clinic and Treatment. Medcoi Journal of Medicine, 15(2). urn:medcoi:article15835.

There are no comments yet

Or use one of these social networks