Tularemia (Туляремия)

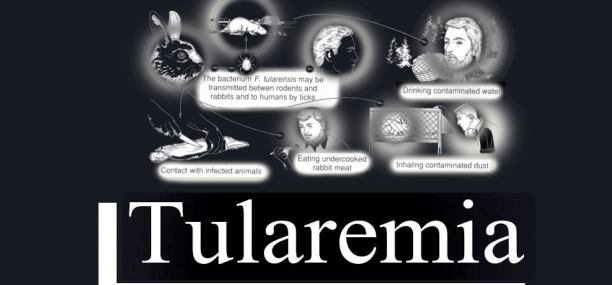

Tularemia, also known as rabbit fever or deer fly fever, is a severe acute infectious disease caused by the gram-negative anaerobe bacterium Francisella tularensis. This pathogen is associated with a range of symptoms, including cutaneous lesions typically appearing as ulcers at the site of infection, accompanied by fever and weight loss. Tularemia is classified as a zoonotic disease, meaning it can be transmitted from animals to humans, with various vectors implicated in its spread, such as ticks and deer flies. Without prompt and appropriate treatment, tularemia can be life-threatening, underscoring the importance of timely medical intervention

| Classification (Tularemia (Туляремия, التولاريميا) ): | |

| Cutaneous forms of tularemia | Visceral and lymphatic forms of tularemia |

| 1. Bubonic tularemia

2. Ulceroglandular tularaemia 3. Oculoglandular tularaemia

4. Anginal-bubonic 5. Other forms of tularaemia |

1. Pulmonary tularaemia

2. Gastrointestinal tularaemia

3. Generalized tularaemia 4. Tularaemia, unspecified |

Pathogen – Francisella tularensis

Epidemiology: see “Plague”.

Clinical picture

Upon exposure to Francisella tularensis, the bacteria responsible for tularemia, the incubation period typically spans from 3 to 7 days before symptoms emerge. The onset of the illness is marked by a sudden and acute presentation, often characterized by symptoms akin to an intoxication syndrome. These may include intense chills, high fever ranging from 39 to 40 degrees Celsius, severe headache, dizziness, muscle aches, vomiting, and profuse sweating.

Additionally, individuals with tularemia may experience lymphadenopathy, a condition where various groups of lymph nodes become enlarged and tender. The face and eyes may appear reddened and inflamed, with the conjunctiva (the membrane covering the inner surface of the eyelids) and sclera (the white part of the eye) showing signs of irritation.

Furthermore, individuals affected by tularemia may exhibit symptoms indicative of hepatosplenic involvement, such as liver and spleen enlargement, which can manifest as abdominal discomfort or pain. These varied symptoms collectively characterize the acute phase of tularemia, necessitating prompt medical attention for proper diagnosis and management.

Bubonic form of tularemia

In the bubonic form of tularemia, one distinctive manifestation is the presence of tularemic buboes, which are enlarged lymph nodes resembling nuts in size. These buboes are typically slightly painful to the touch but are not firmly attached to adjacent lymph nodes or the surrounding subcutaneous tissue. Additionally, the skin overlying the tularemic bubo typically does not exhibit any visible changes, remaining unchanged in appearance. This characteristic presentation of bubonic tularemia aids clinicians in distinguishing it from other conditions with similar symptoms, facilitating accurate diagnosis and appropriate treatment.

Ulceroglandular form of tularemia

In the ulceroglandular form of tularemia, the disease typically begins with a primary lesion at the site of infection, progressing through several stages of development. Initially, there may be small spots or redness at the site, which can evolve into raised papules or fluid-filled vesicles. Eventually, these lesions may ulcerate, forming open sores or ulcers. Concurrently, regional lymphadenitis, characterized by inflammation and enlargement of nearby lymph nodes, often develops. This progression of symptoms is a hallmark of the ulceroglandular form of tularemia, aiding in its diagnosis and differentiation from other conditions.

Ophthalmic -bubonic form of tularemia

In the ophthalmic-bubonic form of tularemia, distinct symptoms manifest primarily in the eye and nearby lymph nodes. One notable characteristic is the presence of follicular proliferation in the conjunctiva of the eye, indicating inflammation and irritation of the eye’s surface. Concurrently, a bubo, or swollen lymph node, may develop in the parotid or submandibular region of the neck. This combination of ocular and lymphatic symptoms is indicative of the ophthalmic-bubonic form of tularemia and requires prompt medical attention for diagnosis and treatment.

Anginal-bubonic form of tularemia

In the anginal-bubonic form of tularemia, the primary infection affects the mucous membrane of the tonsils, leading to inflammation and irritation in this region. This inflammation can result in lymphadenitis, or swelling of the lymph nodes, particularly in the tonsils, submandibular, and neck areas. The presence of swollen lymph nodes in conjunction with symptoms affecting the tonsils is characteristic of the anginal-bubonic form of tularemia. Early detection and appropriate medical intervention are essential for managing this condition effectively.

Pneumonic tularemia

In pneumonic tularemia, the disease manifests as a prolonged and severe form of pneumonia, characterized by inflammation and infection in the lungs. This condition often leads to the development of specific complications, such as abscesses, bronchiectasis (damage and widening of the airways), and pleurisy (inflammation of the tissues surrounding the lungs). The prolonged course of pneumonia and the potential for complications underscore the seriousness of pneumonic tularemia and highlight the importance of prompt medical attention and appropriate treatment to manage the condition and prevent further complications.

Distinguishing tularemia from other diseases is crucial for accurate diagnosis and appropriate treatment. The differential diagnosis involves considering various conditions that may present with similar symptoms. These include bubonic plague, characterized by swollen and painful lymph nodes; non-specific lymphadenitis, which is inflammation of lymph nodes without a specific cause; Hodgkin’s disease, a type of lymphoma affecting lymphatic tissue; tuberculous lymphadenitis, caused by tuberculosis infection; infectious mononucleosis, a viral infection causing fever and swollen lymph nodes; benign lymphoreticulosis, a benign condition affecting lymph nodes; rat-bite fever, transmitted by rats and characterized by fever and rash; lobar or focal pneumonia, bacterial lung infections affecting specific lung lobes; pneumonic plague, a severe form of plague affecting the lungs; pulmonary tuberculosis, a bacterial infection affecting the lungs; and psittacosis, a bacterial infection transmitted by birds and causing pneumonia-like symptoms. Conducting a thorough evaluation and considering the patient’s medical history, clinical presentation, and diagnostic tests can help differentiate tularemia from these other conditions and guide appropriate management strategies.

Laboratory diagnosis

Laboratory diagnosis plays a critical role in confirming tularemia infection and guiding appropriate treatment. Blood analysis typically reveals specific changes, including leukocytosis, neutrophilia in the early stages, leukopenia, lymphocytosis, and an accelerated erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR).

Imaging studies such as chest X-rays are performed to assess for pneumonia in individuals suspected of having tularemia. Ultrasonography is utilized to examine lymph nodes, aiming to detect any abnormalities suggestive of tularemia infection.

Bacteriological analysis involves culturing discharge obtained from buboes, sputum, ulcers, and other sources. Francisella tularensis can be cultured from various specimens, including sputum, wounds, pleural fluid, blood, lymph node biopsies, and gastric washings. However, it’s important to note that bacteriological culturing poses risks to laboratory personnel.

Indirect fluorescent antibody testing is a rapid and specific method for microscopic examination of tissue and smear specimens using fluorescently labeled antibodies.

Serological analysis involves blood tests to detect antibodies against Francisella tularensis. This can be done using techniques such as latex agglutination or enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) assays may also be utilized to detect the presence of F. tularensis DNA in clinical samples.

A positive predictor of tularemia infection is an agglutination titer with tularemia antigen greater than 1/160, which is indicative of infection and warrants initiation of treatment.

The tularemia skin test, involving the injection of tularemia antigen into the skin, can produce local reactions such as edema, infiltrate, and hyperemia within 24 to 48 hours, aiding in diagnosis.

Treatment

Causal treatment:

Treatment for tularemia focuses on eliminating the bacteria using antibiotics. Streptomycin at a dosage of 1g per day or tetracycline at a dosage of 1.2 to 1.5 g per day for 8-10 days are commonly used as the drugs of choice.

Pathogenetic therapy may involve the use of the tularemia vaccine, although it’s worth noting that this live attenuated vaccine is no longer produced due to safety concerns, uncertainties about its attenuation, and production challenges. Desensitizing agents may also be employed as part of pathogenetic therapy.

Additionally, symptomatic treatment may include the administration of vitamins and cardiovascular agents to support overall health and manage symptoms.

Symptomatic treatment for tularemia may involve the administration of various vitamins and cardiovascular agents to support overall health and manage symptoms effectively.

Vitamin C: Known for its antioxidant properties, vitamin C plays a crucial role in immune function and may help to boost the body’s defenses against infection. A dosage of 1000 mg per day may be beneficial for overall health and immune support.

Multivitamins and Multiminerals: A comprehensive multivitamin and multiminerals supplement can provide essential nutrients that support overall health and help maintain proper immune function. These supplements often contain a combination of vitamins (such as vitamin A, vitamin D, vitamin E, and vitamin K) and minerals (such as zinc, selenium, and magnesium) that are necessary for various physiological processes in the body.

Cardiovascular Agents: Depending on the individual’s cardiovascular health and specific symptoms, cardiovascular agents may be recommended to manage symptoms such as fever, inflammation, and pain. Here are a few examples:

- Aspirin (Acetylsalicylic Acid): Aspirin is commonly used as an anti-inflammatory and antiplatelet agent. It can help reduce fever, inflammation, and pain associated with tularemia. Additionally, aspirin’s antiplatelet effects may help prevent blood clots, although its use should be carefully monitored, especially in individuals with bleeding disorders or gastrointestinal issues.

- Nonsteroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs (NSAIDs): NSAIDs such as ibuprofen or naproxen may also be used to reduce fever, inflammation, and pain associated with tularemia. These medications work by inhibiting the production of prostaglandins, which are chemicals in the body that contribute to inflammation and pain.

- Antipyretics: Antipyretic medications such as acetaminophen (paracetamol) may be used to reduce fever and discomfort. Acetaminophen works by inhibiting the production of prostaglandins in the brain, which helps to lower body temperature.

- Beta-Blockers: In some cases, beta-blockers may be prescribed to manage symptoms such as tachycardia (rapid heart rate) or hypertension (high blood pressure). Beta-blockers work by blocking the effects of adrenaline on the heart and blood vessels, thereby reducing heart rate and blood pressure.

It’s important to note that the choice of specific vitamins and cardiovascular agents, as well as their dosages, should be determined by a healthcare professional based on individual health needs, medical history, and any other medications or supplements being taken. Always consult with a healthcare provider before starting any new supplement or medication regimen

Verified by: Dr.Diab (March 30, 2024)

Citation: Dr.Diab. (March 30, 2024). Tularemia Classification Epidemiology Clinic and Treatment. Medcoi Journal of Medicine, 6(2). urn:medcoi:article16383.

There are no comments yet

Or use one of these social networks